If you were signed up to receive my blog, I've moved! I have a new website at lindamackillop.com. Please come on over and sign up to receive updates over there!

Appreciate your support.

Linda

An Opsimath's Journey

Friday, December 8, 2017

Monday, September 25, 2017

A New Novel Worth Persusing

Debut author Katherine James' discomfort with self-promotion has led her to share photos of dogs on social media promoting her new book. But some of us who deeply enjoy and respect her writing feel it's worth helping her out with a human voice. :)

In her novel, Can You See Anything Now?, an eclectic group of characters find their lives overlapping in the small town of Trinity when tragedy strikes, all with unexpected results. The novel features a suicidal painter and her evangelical neighbor, the town therapist, and a college student and her troubled roommate in this gritty, grace-filled story.

To hear directly from Katherine about why she decided to write a novel when so many bookstore shelves already are filled with both new and old books worth reading, take a peek at her behind-the-scenes blog post here.

Pre-ordering is available now by going to Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or Paraclete Press.

In her novel, Can You See Anything Now?, an eclectic group of characters find their lives overlapping in the small town of Trinity when tragedy strikes, all with unexpected results. The novel features a suicidal painter and her evangelical neighbor, the town therapist, and a college student and her troubled roommate in this gritty, grace-filled story.

To hear directly from Katherine about why she decided to write a novel when so many bookstore shelves already are filled with both new and old books worth reading, take a peek at her behind-the-scenes blog post here.

Pre-ordering is available now by going to Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or Paraclete Press.

Wednesday, August 9, 2017

So Much Sky

An excerpt from my empty nest essay, appearing in the latest issue of "Under the Sun" literary journal.

The note appears hooked to the knob of my front

door, a warning. The emerald ash borer disease has ravaged the hundred-year-old stately ash trees lining our road, and our city has

decided to take them all down. The forty trees that spread their canopies over

the length of six blocks like cupped protective hands will be removed as a

permanent solution to cure the infestation. The city offers a plan to replace

the trees in the spring with saplings, but how do you replace a tree that took

a hundred years or more to grow its roots down deep while sending branches

toward the heavens? And saplings come with no guarantee of surviving even

one brutal Chicago winter with its hostile winds and temperatures.

The note appears hooked to the knob of my front

door, a warning. The emerald ash borer disease has ravaged the hundred-year-old stately ash trees lining our road, and our city has

decided to take them all down. The forty trees that spread their canopies over

the length of six blocks like cupped protective hands will be removed as a

permanent solution to cure the infestation. The city offers a plan to replace

the trees in the spring with saplings, but how do you replace a tree that took

a hundred years or more to grow its roots down deep while sending branches

toward the heavens? And saplings come with no guarantee of surviving even

one brutal Chicago winter with its hostile winds and temperatures.

Gusty autumn winds have already stripped the trees

bare. I stare at the silhouetted branches most days as I come and go, as I

stand in the living room holding a warm cup of tea, watching neighbors walk

their dogs. The demise of the trees creates grief as I prepare to say goodbye

to their shade that protects me while I read in the yard, goodbye to the

whispers I hear through my open window on windy days, the haunting call of

leaves brushing together like two hands meeting in applause.

Wednesday, June 7, 2017

Spoken Blessings

Today I have the privilege of writing over at The Mudroom blog, "a place for stories emerging in the midst of the mess."

When my twin sons accidentally caught 17-acres of land on fire while filming a World War II movie with their high school friends, it wasn’t the scorched trees I remember most. Or the helicopters flying over head to drop water. Or even the news stations capturing the flames on camera. It wasn’t the shots of nearby residents emptying their million-dollar homes of irreplaceable objects in case the fire took over.… Continue reading over at the Mudroom Blog.

Friday, May 19, 2017

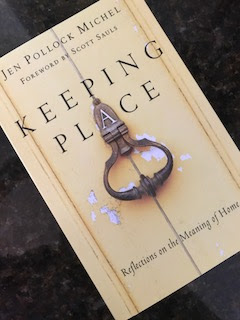

Keeping Place

In my last blog post, I reflected on my own longing for home and simply mentioned Jen Pollock Michel's book, Keeping Place. I've been needing a book like Jen's for a very long time as she addresses many of my own reasons for always longing for home. I believe others will find her book to be a rich read. Today, I'm posting a Q&A with Jen, allowing her to speak about her reasons for writing this book.

Why write a book

about home? Is it your experience as a wife and mother that most informs this

book or something else?

There’s no doubt that my experience of making a home for my

family these past twenty years has informed the writing of this book. But Keeping Place isn’t only meant for wives

and mothers. In fact, I think the longing for home is a human longing. It’s not particular to women. Men feel it, too—even

if they might characterize that longing in different ways.

I’ve spent my entire life searching for home. Partially this

is because I’ve experienced so much loss in my life: the premature death of my

father, the suicide of my brother, a sometimes emotionally distant relationship

with my mother. It’s also true that home has been elusive simply because I’ve

been so geographically mobile, somehow ending up in Toronto as an American

expat.

These life experiences springboard a Scriptural exploration

throughout the book. I want to hear what God has to say about the longings for

and losses of home.

What’s the challenge

of writing a book about home for both women and men?

I recently had coffee with a young woman from church, and at the end

of our conversation, she said that she looked forward to my book on

“homemaking.” Later, I couldn’t help but wonder if she imagined a book of

recipes, table setting ideas, and the best way to organize a linen closet.

I think that’s the fear: that men will see a book on the topic of

home and immediately think it’s a book meant for their wives or mothers or

sisters. That’s why the history of home is a really fundamental part of this

book (chapter 2). I want to trace how home was once a shared space for

residence and commerce and industry up until the Industrial Revolution. That

historical analysis might sound sort of heady, but it’s really meant to provide

a backdrop for the way that we read the Bible, which never talks about “home”

as something which women are solely responsible for.

What books have

influenced you to keep a wider perspective in your home-keeping?

I really do see Keeping

Place as having resonance with a lot of the great work that’s being done on

theology of place. In particular, I really appreciated the early chapters of

Craig Bartholomew’s Where Mortals Dwell,

because it makes the case for God’s good gift of place. I have also loved books

like C. Christopher Smith and John Pattison’s Slow Church, which I believe help us see the role that the local

church can play to “keep place” in our cities. And a perennial favorite is also

Kathleen Norris’s The Quotidian

Mysteries. Beyond that, it’s always been important to me to read outside of

my own experiences: books like Kent Annan’s Slow

Kingdom Coming and D.L. Mayfield’s Assimilate

or Go Home would be two examples.

How do you combine

motherhood, writing and speaking? How does your home-making life practically

work in the day-to-day?

A lot of my day is taken up with the practical care of my

family, especially because I’m the primary parent for our five kids. And even

though I’m the first person to try and find help when I need it (I pay someone

to clean my house, someone else to do virtual assistant work for me), there’s

also something irreducible about the labor that love requires. I have five kids

and a very busy executive husband, which means that my work life is sometimes

more constrained than I would like it to be because of my responsibilities at

home. I can’t accept every speaking invitation I want to. I can’t write on

every topic that interests me. I can’t stay connected on social media (even if truthfully,

I don’t really want to). But I think this is what it means to be human. We are

limited.

Who do you hope is

reading this book, and what do you hope they will gain?

I suppose it’s fair to say that women like me will probably

read the book, and I hope that they’ll come earlier to the realization that

their home is a shared responsibility with their husbands. This “sharing”

benefits children, for sure—who need both mom and dad fully engaged at home. It

also gives women permission when other God-given callings sometimes call us

away from home.

But I hope it’s not just women like me reading the book. I’d

love to see women and men who aren’t married, who aren’t parents, find ways

they can have and make home today, especially in their local churches and

communities. I’d like for people to catch a vision for justice in the world—to

see that the gospel isn’t solely a spiritual endeavor to save souls but that it

also inspires practices of caring for physical bodies and environments.

And if I could just dream a bit, I’d love for someone on the

margins of faith, maybe even on the outside looking in, to read this book and start

making sense of the life and death, resurrection and return of Jesus Christ.

Sadly, when we get to telling that story, we often use a vocabulary that people

are not familiar with. But what if we could talk about the promises of the

gospel through the lens of home?

Last question: isn’t

there a DVD video series to accompany the book?

There is! It’s meant as a teaching companion to the book,

and what I especially love about the videos (and something I can claim NO

credit for) are the personal stories shared in each of the five sessions. Women

talk about their dreams for home, their disappointments of home. I think it

makes it really relevant to our everyday lives. You can watch the trailer here or

buy the DVDs at ivpress.org.

Buy:https://www.ivpress.com/keeping-place (30% Promo code for book/DVD: READKP)

Watch DVD trailer: https://www.ivpress.com/keeping-place

Excerpt: http://wp.me/P3GUgu-12H

Tuesday, May 16, 2017

Homesick

Our family loves to drive past our old homes in

Massachusetts and Virginia, trying to catch a glimpse and a memory of the rooms

we once inhabited, the place where we loved and laughed, cried and fought. We critique

the changes the new owners made, wonder why they took down that tree fort built

by our sons’ young hands, cut down the tall trees out back, or why they changed

our favorite paint color.

Recently,

I’ve discovered I can find my old homes online by typing the address into

Google and watching the most recent Real Estate ad pop up. In the case of our

old home in Massachusetts, I caught a glimpse of the rooms where we lived, the

grape arbor in the backyard, the renovations the new owners made to improve the

place.

In the meantime, instead of entertaining fantasies

that the perfect home exists in another state or in my past, I will sit down by

the fire, relish the good and safe conversation in the home I do have as it

images a future home.

In the meantime, instead of entertaining fantasies

that the perfect home exists in another state or in my past, I will sit down by

the fire, relish the good and safe conversation in the home I do have as it

images a future home.

My childhood

friend owns a home in the same Cape Cod neighborhood where my grandparents once

lived. When I visit her, we walk over to my grandparent’s old house and stand

at the end of the driveway. I silently long for my grandmother to walk out the

breezeway door and invite me in for her homemade clam chowder and gather me up

for one more walk along her beach over to the boathouse—our final destination where

we always turned back for home. She’s been gone a very long time.

Once, my twins stood outside our old home in

Virginia after our move to Illinois. The new owner recognized them and kindly

came outside, saying, “You used to live here, didn’t you?” When they nodded,

she invited them inside to take a look. They respectfully declined.

We can never really go home. My twins knew the house

wouldn’t be the same. They knew they wouldn’t find our Brittany spaniel sitting

by the backdoor, watching the squirrels. Their room would be painted a

different color with different furnishings and Godzilla their bearded dragon lizard

would be gone. Their brothers wouldn’t be inside listening to music, playing

guitar, or reading.

.

|

|

Our home during my teen years in Massachusetts.

|

But the irony of longing for these old days, these

old homes, is that while I lived there, I longed for home somewhere else. As a young person, I assumed everyone else’s home

was more peaceful than my own turbulent home. When my sons were growing up and

I had found the family I always longed for, a part of me still longed for a

more ordered home, some idyllic place where I would never feel the anxieties of

this world and the push of needing something,

anything.

I know now that my imagined home doesn’t exist

anywhere on earth. I know this because of my skewed thought process when I look

into lighted windows on my evening walks in our neighborhood, imagining the

lives of the occupants, thinking surely they have fewer problems than me,

better health, more robust financial portfolios. Surely they live in the perfect home, that place where I want

to live. I imagine their lives with symphonic music playing quietly in the

background, the lighting dim and warm, the bookshelves lined with great

material. An easy chair sits by an ottoman laden with stacks of books and

literary journals. Someone reads there with a cup of hot tea by their elbow

while the smell of dinner wafts from the kitchen. In the cold weather, a fire

burns warmly in the room. Voices are quiet or silent in this safe, safe place

where strife ceases to exist.

This imagined home is a mere fantasy, a mirage in

most cases. Many of the homes I pass likely have worries over bills, grief over

the tension between spouses when one reclines in the basement watching sports

for hours on end and one uses their tongue to slice and dice people. But here’s the puzzling part. Why create this

phantom life in my mind when my home today fits the lovely description above, a

comfortable refuge for us and for others who visit? My home may not be luxurious

or fit for Home and Garden magazine,

but it’s the kind of home that just might be the best you can find on earth,

despite its small size and simple furnishings. Everyone feels welcome and safe

here. We enjoy a steady stream of rich company and great conversation around

the table, creating memorable moments.

Yet I continue to imagine home elsewhere as a place where strife truly ceases to exist, where

some sort of internal longing quiets. Even as I write these words, I hear

the absurdity. Could it be, as Jen Pollock Michel writes in Keeping Place, that we are “hardwired”

for a true home? Will our souls only recognize this place when we find it finally satisfies all our longings?

I write about homes a lot, especially old New

England homes with their sturdy construction and the way they’ve passed the

test of time still standing through nor’easters and New England winters. I long

for permanency provided by one of these colonials or farmhouses that when I

walk through their doors, I stop searching for a new and different home. Despite

all the houses where I’ve lived, I’ve never stopped longing or found my true home here. Yet I hear

its call on those evening walks through my neighborhood, on those internet

searches to find my old abode, on those visits to past residences, in my longings to move someplace warmer, less expensive, closer to the ocean. C.S. Lewis

wisely describes this longing in Mere

Christianity: “If we find ourselves with a desire that nothing in this

world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that we were made for

another world.”

Some may attribute my longings to my own failing, my

own lack of contentment and craving for what others have, and at some level,

this may be true. But I know I mostly feel deep

contentment in my life, which adds to the perplexing state of my

longings.

In the meantime, instead of entertaining fantasies

that the perfect home exists in another state or in my past, I will sit down by

the fire, relish the good and safe conversation in the home I do have as it

images a future home.

In the meantime, instead of entertaining fantasies

that the perfect home exists in another state or in my past, I will sit down by

the fire, relish the good and safe conversation in the home I do have as it

images a future home.

I’d love to recommend a more in-depth reflection on

this topic. Jen Pollock Michel’s Keeping Place:

Reflections on the Meaning of Home addresses this innate longing uniquely

and with far more detail than this brief post. I’m so enamored with her book

that I want to buy multiple copies and pass it out to my friends. So many

people long for something this world doesn’t offer. I’d love to hear if you are

one of them. In my next post, I’ll be sharing a Q & A from Jen’s thoughts

on this topic. But for now, enjoy this excerpt from her book: http://wp.me/P3GUgu-12H

In the foreword of Jen's book, Scott Saul writes, "Keeping Place

is both memoir and rich biblical theology, and is, in all of its parts, an

aroma of the Home for which we are made and for which we are destined. With

wit, candor, a good bit of humor, and with transparent glimpses into her home,

her history, her travels, her travails, her worship, her marriage, her table,

her rest, and her longings—Jen offers an oasis for all of us who are homesick."

If

you’d like to receive Opsimath Journey

posts automatically, please subscribe over to the right.

Thursday, April 13, 2017

Everbloom Book

Everbloom is a collection of essays written by women of the Redbud Writers Guild. The pages are filled with their stories of living life with intentionality, purpose, and wisdom as they walk out their faith. I share Catherine McNiel's essay here during this Easter Holy Week with her permission.

Passover, Betrayal, and Deep

Passover, Betrayal, and Deep

Redemption

by Catherine McNiel

S

|

he leans over to

pass the plate of bitter herbs, her shawl grazing the edge of the Passover table. The bitterness is to remind us of our

bondage, our suffering. And my phone rings.

Reaching down to silence the ringer, I recognize the name of

a neighbor I hardly know, rarely talk to, and never call. I ignore it.

“Why on this night do we dip the herbs twice?” My child asks

the traditional question, and our host offers the traditional answer: The

greenness of the herbs reminds us of springtime, of new life. We dip the

parsley in salt to remember the weeping. We dip the bitter herbs in sweetness

to recall that from suffering comes redemption.

And my phone rings again.

Around the table we drink a cup of wine, symbolizing

deliverance— and my phone rings.

We cover and uncover the matzah, a picture of brokenness and

division that will one day become wholeness and unity—and my phone rings.

Finally, I am alarmed enough to excuse myself and step into

the next room. As the rituals of suffering-becoming-redemption are carried out

around me, I struggle to absorb the news from my frantic neighbor: I have been

the victim of a crime. During the reenacting of this Passover I am pulled

away—away from this same reenactment that Judas hastily left so many years ago.

He left this ceremony of suffering and hope to betray. I am pulled away to

discover that I am betrayed.

All through the long dark night my husband and I

search for understanding. Silent car rides, meetings with police,

confrontations with the accused. We stand outdoors in the cold, looking through

windows—our windows—from the outside. Standing in darkness, peering into a

dimly lit room, wondering how to get from where we are back into the light.

***

We had moved recently, and our condo, our first home,

was under contract to be sold. Everything about this change was outside my

comfort zone. The market was poor, and the financial hit was staggering. The

process moved forward on a knife’s edge. And then, just weeks before closing,

on Passover, came the unbelievable news that someone we knew had broken into

our now-empty home, moved herself in, replaced the locks, drawn up a forged

lease, and called it her own.

Amazingly, the law was not on our side; at least not

at first. Squatter laws—written with vulnerable women and children in mind—give

rights to whoever lives on a property currently, however shaky their legal right

to be there. The same laws that offer dearly needed justice to unwanted

ex-girlfriends tossed out on the streets by their homeowning boyfriends now put

us in an impossible position. The police believed us, but they could not remove

the woman and her children from our house. The expertly forged lease she waved

in their faces gave them reason even to doubt our story.

For days we held vigil, one of us outside our condo, the

other at the police station. For a week, this went on day and night.

It was Holy Week.

Our vigil kept us from marking the sacred days: Palm

Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, Holy Saturday. But the liturgy and its

meaning are written so deeply into my soul that the words echoed through my

mind all the same.

So it happened that while I reflected on Holy Week and the

alchemy of redemption in Christ—in whom death, sin, pain, suffering, injustice,

forgiveness, and love are mingled—in the same physical and mental space, I

suffered pain and searing anger, strained for justice, encountered injustice,

and longed to be known and vindicated, to forgive and be forgiven, to love and

be loved.

Above all, I

pondered redemption.

***

Late at night on Friday, Good Friday, we received a call

from the police. New information had been uncovered, and the woman who stole

our house had been arrested on other charges, and her children removed. While

we still could not legally clear out her things, have keys made, or take back

our condo (it would require her voluntary change of heart or a sheriff with a

judge’s eviction notice to do that), the police let us in to sort out our own

belongings.

What a poignant and painful thing it was to walk up the

steps to my house—through the doorway where I brought my own babies home from

the hospital on their second day of life; that sanctuary now a place of fear

and pain.

Inside that doorway was another woman’s life, a woman who

also sought sanctuary for her babies. Everything was deceptively arranged as

though she had lived there for months, as the forged lease indicated. Her

things, my things; the two us intertwined without my consent.

In the hours between Good Friday and Holy Saturday, we went

through our-home-that-was-her-home, sorting our things from hers.

Touching with our hands the intimate

mingling of ourselves and our adversary.

Never before or since have I received such a bittersweet

gift, an invitation to see an enemy’s life as she sees it.

Her pantry and her closets. The gifts hiding for her

children’s birthdays, and the homemade presents they affectionately made for

her. The DVDs promising escape and a better life through romance. Postcards

from televangelists promising a get-rich-quick theology. Her intimate hopes and

dreams reflected in everyday things, like those we each gather around us.

In those hours of sorting, I saw how she was raised and how

she lived. I saw what resources she did and did not have, her feisty courage,

her brokenness, her desperate attempts and frightening failures. I saw the

layers upon layers of injustice others had heaped upon her, as well as the

social and systemic abuses in which we all play a part. I saw that these things

were intermingled with her own wrong, illegal, and unjust choices.

But the first and overwhelming thing I saw when I looked at

my perpetrator was a woman who was utterly broken, herself a victim of so much

injustice and pain; and I saw that I could not pick up a stone to throw at her.

Legal recourse, yes, for her sake as well as my own. But even the furious anger

pulsing through me was not large enough to keep down the compassion

and—yes—love I felt for her. From just a glimpse through the lens of God, who

sees all things, I saw she was my sister. Yes, I had filled my life with better

choices—but only after others filled me with better resources, training,

encouragement, and love. That I have these things—unearned and overflowing at

my disposal—does not qualify me to look down on those who do not.

To whom much is given, much will be

required.

Late that night, in the middle of literal and spiritual

darkness, I wrote down this cry for redemption:

She has only processed white flour and sugar, bologna and junk food— no

fruits or vegetables, grain or meat. She has cable in every room but no books,

games, music, or friends. She has letters and promises and formulas for wealth

from God but no evidence of Good News, of Love and Grace. She has tips on how

to win the lottery and a trail of shortlived employment start-date letters and

pay stubs. She has love notes from her babies and school notes reporting their

fights, suspensions, and failures. She has a journal of love songs and poems

and court documents for her divorce and custody disputes.

She has committed crimes against us, lied to and about us, forged legal

documents in our name, broken and entered our house, pushed us to the limits, and

forced the loss of finances and property.

She is lost, scared, and desperate. She has nowhere to go and no one to

help her. She has children and dreams of security for them and for herself. She

is homeless and has a picture of a sprawling California mansion on her

nightstand.

She needs mercy.

We need justice.

My longing is for restoration, but my recourse is the

law.

We spend our working days advocating for the vulnerable, while advocating

in our spare time for her arrest.

I am vulnerable to her crimes, and she is vulnerable

to my rights.

She needs compassion but seeks help through

lawlessness.

She has hurt us and is hurting.

She is the wicked and evil in my life but the broken victim in her own.

I cannot accept a redemption story that does not keep her in its deepest

and most precious heart. You can see her childhood and her past, those things

that molded and broke her, the life built by junk food and junk companionship.

You know it all and more.

This

Easter, and in the final day, what redemption do You have in mind? A new earth

must have room for the living things that both kill us and give us life and for

this woman who is both criminal and precious child.

I am undone.

Rebuild me according to your truth.

As the sun rose, we went home and to bed. My troubled thoughts

wandered to a friend walking through a time of darkness, meandered next to my

children, then to my husband, then to other friends and family in their own

darknesses. I pondered how each person is as valuable to someone as my babies

are to me, that somehow life is both unfathomably precious and utterly

fragile—that God-sized redemption must swallow us all, not merely skim a little

off the top.

***

Just after sunrise, the room floods with light, the scent

of spring flowers, and the sound of bells—the symbolism of new life, of

darkness vanquished, of Good News that interrupts all sounds of weeping. On

this Easter morning my mind is jammed with tortured thoughts, the abstract

theology of Jesus’s triumph over evil juxtaposed starkly with the crime that

has overtaken my life.

She sits in jail this morning. I sit in

church.

Theology, this Easter, cannot be abstract. Suffering,

redemption, grace, sin, and forgiveness stare me in the face and demand an

answer. The pain and anger in life up close means that Resurrection cannot be

limited to the safe domain of songs and stories. It cannot be contained by

those of us dressed up in the pews on Sunday.

Surrounded by jubilant celebration, I can’t help but ask:

What does this mean for her? For my enemy who is my sister? And more, what can

this possibly mean for her-and-me, one entity meant to sit and receive together

the shocking news of Resurrection?

Redemption is wholeness for both of us, not

one of us triumphing over the other.

When he announced his redemption of the world, to the

world, he did not address only those who were only a little broken and could

run to him; he did not overlook those so shattered they could neither hear his

voice nor lift broken arms toward his saving hands. It is not redemption if the

most broken and destroyed among us are not made whole. God’s promise cannot be

limited to me and those like me. If he is to make things new, then redemption

includes my enemies. If God’s redemptive story is true, it is true for the real

world and every ugly, broken thing suffering within it. Resurrection redemption

reaches all the way into death and decay.

The question pulses through me with every breath: if I

understand what Easter is about, how can I celebrate it without her? The

redemption initiated by Christ is not my righteousness triumphing over her

lawlessness. That is simply the righteousness under the law, the former thing.

But now, in Christ, a new mystery is revealed. Resurrection redemption is full

restoration of her life and mine. Restoration of her life with mine.

We cannot truly celebrate alone. After all, in God’s

kingdom the lion will lie down with the lamb.

If I believe Christ’s Easter story in its fullness and

follow it to its conclusion, what can the truth be but this? And if this is

true, what other truth could be large enough to overcome it?

My phone rings again.

The police officer assigned to our case asks to meet me at

the condo; the woman who stole our home has agreed to leave. Even so, the law

states that only she can remove her possessions from our house.

Since she is in jail, her friend is coming

to pack up instead.

A moving crew joins us, and as they carry clothing and

furniture to the truck, they look at me quizzically. “We just moved this stuff

into the condo two weeks ago. What’s going on?”

My job is to be a witness, along with the police, as this

friend boxes the possessions, as the movers carry them out. My heart breaks as

I realize that the “friend” is a sister of a former boyfriend. The two women

haven’t spoken in years—yet this was the closest kin she knew to call at such a

desperately dark hour.

Finally, the empty house is ours again. The sale under

contract can continue toward closing. What was lost has been found. What was

stolen has been redeemed.

At least, for me.

***

“Why on this night do we dip the herbs twice?” On Passover

night, my child asks the traditional question and receives the traditional

answer: The greenness of the herbs reminds us of springtime, of new life. We

dip the parsley in salt to remember the weeping. We dip the bitter herbs in

sweetness to recall that from suffering comes redemption.

This is deep redemption. Not pruning a bit off the top, but

swallowing up from the roots. New Creation must undo and remake every broken,

breaking, destructive piece and turn it to wholeness and life. Only by joining

this story of redeeming power can we ever hope. Not for protection, perhaps, or

safety, but for ultimate salvation and love. The sort of love that, once or

twice in a lifetime, feels so tangible you could reach out and grab ahold of

it.

On Resurrection Sunday, as on Passover, the bitter herbs of

all our brokenness are dipped, twice. In the deepest magic of his redemption,

our suffering and bondage are taken into his fathomless arms—and made green

with new life.

She sits in jail; I sit at home. She chooses deception and

theft against me, while I pursue her conviction. She will lose everything she

sacrificed for; I will recover all I have lost. Deep redemption has not yet

come, for we cannot yet sit together and rejoice, made new and set free. We are

truly enemies.

And yet.

I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels

nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height

nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from

the love of God that is in Christ Jesus our Lord. Even in the darkest hour.

Each of us.

Entirely.

Already.

Regardless.

The matzah crumbling in my hands is broken. But it will be

brought back together. Somewhere in the world-made-new my enemy and I sit and

drink the wine of rejoicing, whole.

Together.

To read the other Everbloom essays, pre-order from Amazon.com, Paraclete Press, Barnes & Noble and Christian Book Distributors

#everbloomthebook

Catherine McNiel is a seeker who writes to open eyes to the creative and redemptive work of God in each moment. She is the author of “Long Days of Small Things: Motherhood as a Spiritual Discipline” (NavPress 2017), and her writing has appeared in numerous books and articles. Catherine serves alongside her husband in a community-based ministry, while caring for three kids, two jobs, and one enormous garden. Connect with Catherine at catherinemcniel.com or on Twitter @catherinemcniel

http://www.catherinemcniel.comTo read the other Everbloom essays, pre-order from Amazon.com, Paraclete Press, Barnes & Noble and Christian Book Distributors

#everbloomthebook

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)